Speculation abounds about how schools will change or need to change in the coming years. Aside from offering occasional speculation on specific elements or forces that might effect this change or offering platitudes I have yet to see many people offer any clear picture of what schools will look like in the coming years. So, at the risk of suffering the speculator's fate of looking ridiculous after the fact I have decided this morning to attempt to offer one concrete forecast of this future that to me lately seems to becoming more clear.

Speculation abounds about how schools will change or need to change in the coming years. Aside from offering occasional speculation on specific elements or forces that might effect this change or offering platitudes I have yet to see many people offer any clear picture of what schools will look like in the coming years. So, at the risk of suffering the speculator's fate of looking ridiculous after the fact I have decided this morning to attempt to offer one concrete forecast of this future that to me lately seems to becoming more clear.To begin, we need to identify the forces that drive public education and identify what schools are for. Education in a broad sense seeks to improve individuals and make a positive difference in the world. Public schools, on the other hand are driven by two more concrete but related goals: 1. Establish an informed citizenry; and 2. Prepare the population for participation in the workforce. With all the talk of change I don't see much change in these goals. What has changed is what is needed from schools to achieve these goals. Specifically, our economy is no longer driven by the type of industry it was at the inception of public schooling.

When this country was founded our economy was a resource economy. People traded raw materials and it was far more common for consumers to use these raw materials to make their own goods. In this time it was far more common, for example, for an individual to make their own clothes than buy them at a store. The industrial revolution was the first big shift in our nation's economy. In the industrial revolution goods were traded. Manufacturers purchased the raw materials and produced goods. It was far less common that individual consumers would make their own goods. For the industrial economy to work efficiently a top down organizational structure was needed for businesses to work. You had consumers who purchased their goods from retailers, who purchased their goods from wholesalers, who purchased their goods from manufacturers, who purchased their raw materials from farmers and miners and employed consumers to produce the goods. This demanded industries to form corporate structures where one CEO oversaw a hand full of managers who usually oversaw a handful of other more task specific managers who oversaw workers.

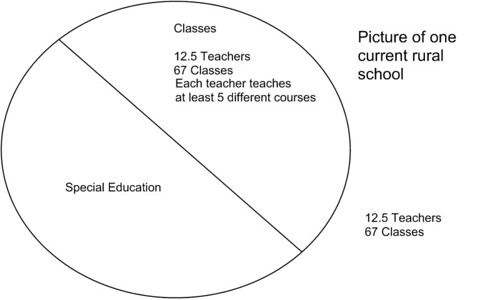

This time period also saw a rise in public education and much of our current school model is based on the demands of the industrial economy. Schools then looked a lot like factories both in how instruction was delivered and how they were managed. A superintendent oversees the work of principals who oversee the teaching staff of the schools they manage who do the work of delivering instruction to large groups of students. For efficiency subjects were segregated and students were moved along through a traditional work day through strictly regimented time schedules. Of course, this system proved over time to be ineffective at achieving universal achievement goals but it did allow the state to offer universal access to an education that would prepare students for the industrial workforce.

What changed? The economy is moving from a goods based economy to an experience based economy. Customization of goods is the order of the day. Where in the industrial economy goods are treated as raw materials, our new economy treats personalized goods as raw materials. This top-down approach to organization proves to be ill suited for this new economy. Our recent economic meltdown is evidence of this. This past Christmas shopping season is a clear indicator of what business models work in the new experience economy. Retailers steeped in the top-down approach had dismal sales reports. Many have already gone out of business. Retailers such as Macy's have had to close many of their stores. On the other hand, stores like Walmart and Amazon.com who remove the middle-man and put consumers in direct contact with manufacturers fared better. This new economic structure will be the main force that changes public education.

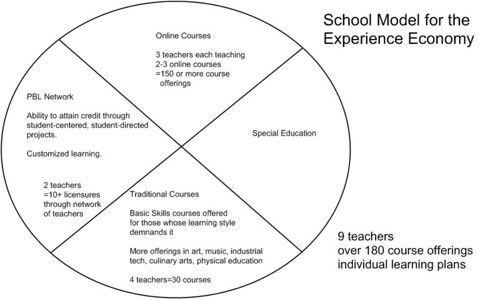

So, how will this happen? The biggest force I currently see driving this change in public education is online learning. It is far cheaper to deliver an online course than a face-to-face course. The cost factor alone is a huge drive behind it. Advances in technology are every day improving the quality of an online education. Rather than speak in nebulous terms I will now turn to more concrete examples. In southeast Minnesota there is a group called the Southeast Service Coop that is offering to schools online courses. For a nominal fee your school can become part of this coop who in turn will train up to three teachers how to deliver online courses and how to develop online courses. Those teachers then have the choice of owning their courses, meaning that they are paid directly from the coop based on enrollment numbers or they can choose to keep their employment status with their school and the school assumes the risk. Should that teacher's class be in high demand the school or the teacher are compensated at a profit. Should that teacher's course not attract enough students it is marked as a loss. With this system, three teachers working in one school could bring with them them hundreds of course offerings in every content area. This will be especially beneficial for small schools that are limited in how many courses they can offer.

If the coop were to integrate student or parent rating systems to rate the quality of specific courses or leave comments about the class (the same way Amazon allows customers to rate products) the motivation for a teacher to offer higher quality courses and instruction is driven by demand. Knowing that should students not find your course useful or engaging that they will be less likely to take your course or knowing that if you provide a good course that

students will likely suggest it to others will build accountability into the system that the traditional model simply doesn't have. School choice makes the consumer (the student and their families) the employer (or administrator).

students will likely suggest it to others will build accountability into the system that the traditional model simply doesn't have. School choice makes the consumer (the student and their families) the employer (or administrator).However, not every student does well in an online class and not every class is well suited for online instruction. There will still be a need for face-to-face classes. The benefit though, is with the online courses being far cheaper to offer than face-to-face classes more money can be diverted to courses that are done better face-to-face. This could see a rise in domains such as art, music, industrial technology, home economics, physical education. This rise will also be driven by the experience economy, what Daniel Pink refers to as the "Creative Class".

Not every student does well in traditional face-to-face courses either. That is one reason we have special education. I don't see significant changes in how schools offer special education services. The one change I foresee is with more and more core courses being offered online special education teachers may find themselves teaching more core subjects to their students using the student's enrollment in an online course as the curriculum.

The industrial school model also is flawed in it's ability to address multiple learning modalities. Inherent in the system is a bias for concrete-sequential thinking, a trait highly valued in the industrial age. Not all learners are concrete-sequential thinkers though and alternative teaching/learning methods like project-based learning have proven to be more effective for many. A fourth department is needed in the new school that allows students to direct their own learning and tap individual interests and talents to motivate growth. In this quadrant of the new school model teachers serve as student advisers and students attain school credits through authentic learning tasks. These PBL advisers in smaller schools can be connected to others in a network establishing networked teams of teachers covering all license areas.

Contrast this model with the current model. Under the current model, the average teacher in a small rural school teaches an average of five different courses. That is five curriculums to develop and manage, five different daily lesson plans, and often these teachers also teach some middle school or elementary school courses. With this new model teachers average only 3 courses that they have to administer while more than tripling the options available to students. When you put families in charge of quality control that further eliminates the need for some management positions. The need for a school administration is also eliminated if the teaching staff (perhaps the student advisers) served as teachers in private practice and shared administrative duties. Essentially, schools in the future will look more like community education centers.

No comments:

Post a Comment